When colonial powers ruled African nations, it was because they had little understanding of the rest of the world and the nature of human behaviour. You got this from exposure, travel, and education. True, traditional education had its merits: you learned the family trade informally from your parents and relatives when young: how to till the land, grow crops, use manure, catch fish or hunt the best animal and even select good seeds and breeds of domesticated animals.

It is also about life: respect for elders, care for siblings, hard work, and management of personal resources; yet it is about the importance of family cohesion, unity between the fallen and the living, and defence of family values.

Colonial spies learned early on that to ruin a nation, a community, or a clan, all one needed was to break their confidence in themselves, make them think there were better values, which would bring more prosperity; there were better beliefs, even better ancestors, which would take them further than what the existing would, and even better knowledge, which others had used and were much better than themselves.

By slowly convincing local leaders, they obtained fake contracts drawn in a foreign language and signed by ignorant local leaders who could not read and hence did not know their contents. This is how the in-famous chief Mangungu and others got trapped and gave away our land, opening up the motherland for colonial rule and exploitation.

Also read Faith and Doubt in the Digital Age: How Social Media Shapes Beliefs

Similar stories will be told in Zimbabwe, South Africa, West Africa, and even North America. Forests were brutally harvested, elephants and other animals hunted for their tusks, horns or skins, minerals dug and taken away for the price of a few boots, pieces of cloth and beads for the local rulers.

A railway was built to carry the loot, using iron from the same motherland. New religions were brought in: Christianity, Islam, and Judaism were taught to be more actual beliefs and ways towards perfection than the old native African beliefs that we went to the next world with blessings from our elders and forefathers. The former were described as coming from the devil, and the forefathers were their agents, mizimu. In contrast, the forefathers of the colonialists were the blessed sons and daughters, saints, of the Almighty.

Education and The Promise of Development

Evolution of the conception and practice of education: Discussions on education focus on what it means to educate an individual, a community, or a society, develop and strengthen knowledge, and liberate a person and, later, the community. This usually takes the form of a curriculum, revised occasionally depending on society’s reflections on what and how this can best be done.

Developing (educating) the individual learner: To students of education, educating the learner is reflected from two opposing perspectives. One is based on the belief that a young person coming to school has little relevant knowledge of a new language other than the mother tongue and, hence, must be taught the proper language.

Even the mother tongue, learned from an illiterate mother and father [or relatives and friends living in the slum], may not be the standard language acceptable in the society, especially by the rulers. Children entering school must remove the home language and expressions acquired from home and learn the official language adequate to the ruling class. The home language cannot be used at the residence of the local chief, let alone the colonial Bwana Shauri (district commissioner).

Specially trained people must teach this “official” language, and after one has acquired it, one can be “certified” and allowed to speak at the people’s court or public office and even to teach others. Language was, therefore, one important “subject” at the school. This had two components: the formal local dialect [e.g. standard Kisukuma kihehe, or Kihaya] and then the lingua franca, Kiswahili, which also had a vernacular and a formal language.

The vernacular was used in the shanty and local village compounds, and the formal was used in schools, courts, political discourse, and writing. Then, we had other “subjects” that the school had to teach. One included acceptable manners, which in traditional society included how to conduct oneself at the homestead of the local chief and later at the office of Bwana Shauri or the district commissioner.

Local customs, mannerisms, laws, and regulations could not be taught at home, such as how to ask for permission to speak in a large meeting, how to explain something important to a group, and even how to treat simple injuries, feed the young and old, prevent diseases, etc. An individual who had acquired this was considered civilized and, hence, could be given the reins of leadership and power.

Also read Should We Encourage International Cooperation as a Strategy Against Climate Change?

The other assumption was that every individual had an inborn talent and knew something about everything. Hence, he or she was not coming to ‘school’ to be ‘taught’ in the real sense but to be allowed to share his/her knowledge acquired from home with others who also had talent and had acquired knowledge from their parents and family.

This is different to coming to be “taught” and removing the “corruption” or wrong knowledge they had from home, but rather to share that unique value and talent they were born with or had learned from home with their peers and community. This included language, knowledge of plants, animals, soil, manners, speaking, etc.

It would grow as they stayed in school, but it was not “evil” to be changed by schooling and “education.” Education was a process of learning from others, furthering knowledge, and growing intellectually, physically, morally, etc.

The conflict between these two beliefs is that a person enters school to learn what he does not know. The other is that he comes to develop or share what he has brought to the school with others, and the whole group grows their knowledge base during the process.

This has plagued education for a long time and was a big reason some people thought they had an obligation to educate others by teaching them what they had been socialized to do and labelling what the others knew as nothing important, pagan, kaffir, or pseudo-knowledge to say the least. This colonial attitude among teachers is used in our schools today.

Developing The community/society: From the belief that a person came to school to remove the wrong they had and put it right, and the other that they came to share the good they had, led to an extrapolation to the community also being civilized by being taught the right culture, knowledge, values.

This process was called enculturation, conversion, or even civilization. Today, they will say a community is civilized when they mean it has forgotten its primitive culture and acquired modern culture. If one examines this contemporary culture, one finds a negation of some outstanding values of the past in favour of values brought in by other people.

This hegemony thrives today, where Africans despise their culture and are unable to teach their children their vernacular language, cuisine, and traditions. I am surprised that in a postgraduate class I have been teaching for the last 30 years, the proportion of students who know their mother tongue has decreased from about 30% in the mid-1980s to less than 10% today.

If you survey a university student population of 1000 students today, hardly 20% will know their mother tongue; hence, they cannot even research in their local community. Young parents with children growing up in middle-class families in Dar es Salaam today are working hard to send their children to English medium schools and speak English to them at home.

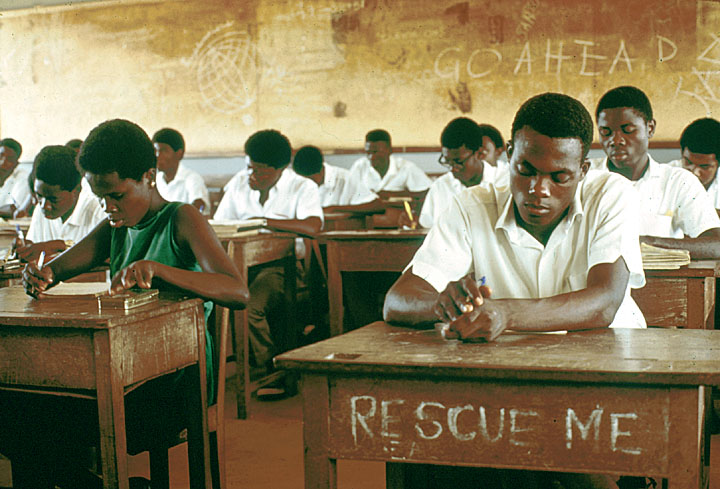

You wonder if these people are going to live in an English-medium country. Children studying in Ward Secondary schools have teachers with low English proficiency and also a low content knowledge base. The products are funny, and one wonders whether they will be able to take this country to the fourth Industrial revolution, where Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence are dominant.

In my next article, I will develop the idea of what children learn from their teachers:

Encouraging knowledge development, developing critical thinking, individual liberation, acquiring the self-reliance spirit, and competing in the modern world by knowing their national wealth and values and using these to make it in a brutal global environment.

To be honest most Tanzanian university students can barely speak English and that is more alarming considering they supposedly learn their academics in English instruction from secondary school thru University