Carpetbagging: an outsider who pretends to be an insider is a carpetbagger; he’s a person who tries to take advantage of a group by joining it only for his benefit. It is loosely defined as opportunistic, self-seeking and exploitative outsider-seeking and securing public office. In elective democracy, these individuals dwell in another area but run for elections in constituencies where they are not permanent residents.

The history of carpetbagging began in the US after the Civil War when a Northerner had ambushed the South and became super active in Republican politics, cashing in on the unsettled social and political conditions of the area during Reconstruction. Since then, carpetbaggers have become mercenaries in the political vocabulary, and many have come to tolerate or emulate them without fear of retaliation or rebuke.

Most carpetbaggers in Tanzania invoke identity politics of association with their voters and their constituencies. Ethnic, filial, and childhood upbringing coalesce to justify a carpetbagger to seek to represent voters and constituencies they do not live in, essentially ending up with representation that is divorced from reality.

Carpetbaggers tend to be unfamiliar with the challenges of the constituencies they represent, so they hire personal assistants from those areas who jot down problems for them that they can present to Parliament. Most carpetbaggers in Tanzania are found in Parliament and, to a lesser degree, in the Councillor position.

The real reason why carpetbaggers flock to the parliamentary constituencies is earning money, and when it comes to Tanzania, it is some serious cash. So, carpetbaggers transfer jobs from the residents in those constituencies to their permanent residences.

Even if you look at where the earnings go, you will see most wages earned by the carpetbaggers seldom are invested in the constituencies they represent, save for menial jobs they hire as drivers, assistants and the like. Most of those earnings are invested in real estate where the carpetbaggers live elsewhere but seldom in the constituencies they represent. It is a flagrant wealth transfer, but few have given it some worthy consideration!

So, overall, carpetbaggers are bad news to our representative democracy: they steal jobs from the locals, they barely know the challenges in the constituencies they represent because they are not permanent residents of those areas, and worse, they rarely return the favour by investing in the constituencies they represent, save for the CDF (Constituencies Development Funds)

The path to end carpetbagging is ridden with boobytraps because most parliamentarians are carpetbaggers. Therefore, they are incentivized to kill such a legislative initiative, knowing they will never send themselves to an earlier retirement.

If carpetbagging is outlawed, most MPs must relocate from Dar-es-Salaam to their constituencies to meet statutory permanent residential requirements.

Specific Case Studies Recapped

In the 1995 parliamentary elections in the Karatu constituency, pitting a political veteran, Patrick Qorro, against a political neophyte, Dr Wilbard Slaa, one thing stood out above everything else to the voters. The biggest political problem that was decisive in that election was the lack of running water in the spigots.

During the campaigns, the electorate wanted either of the two candidates to expound on how they would fix the water shortage problem. Dr. Slaa, being a permanent resident, had better ideas and was intelligent and savvy enough to seek funds from various donors and begin solving the problem.

He liaised with NGOs, government entities, hoteliers and residents to address the water shortage problem. While Qorro was on the stump, he was remonstrating, nonplussed and using unsavoury language, which put off the electorate. Qorro was being pushed to the gullet of the voters by the then CCM presidential candidate Benjamin Mkapa, who went a distance to promise the Karatu residents goodies under his watch if Qorro was elected, but voters had other ideas. Dr. Slaa sailed through, leaving CCM to massage their loss. The lesson there was carpetbagging may not work where competitive politics prevail.

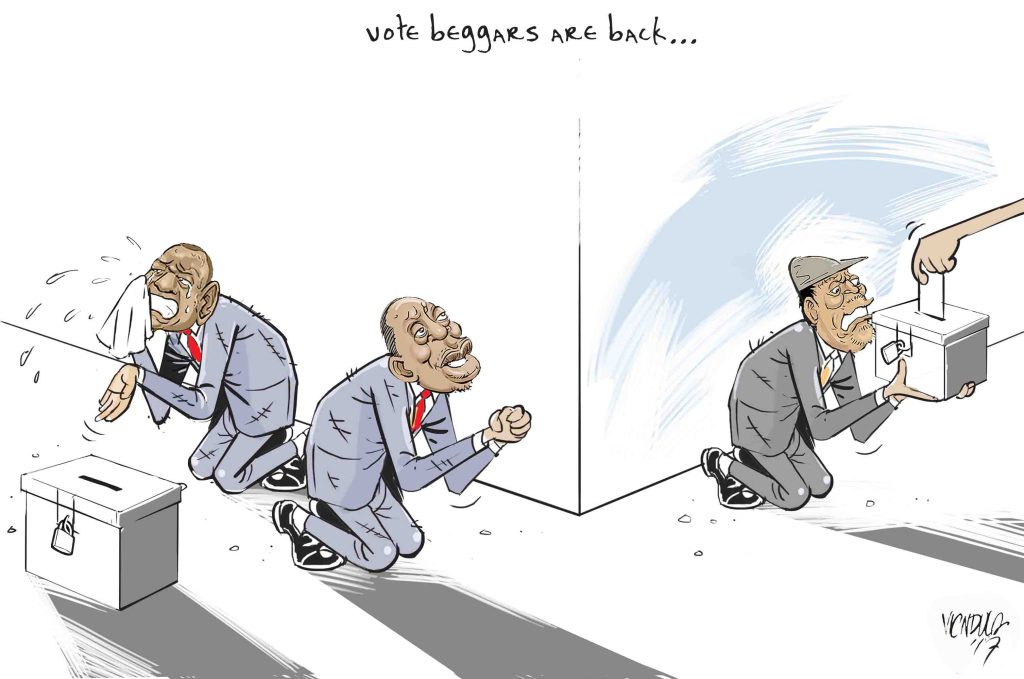

In other similar cases, we have witnessed carpetbaggers throwing themselves on the ground, kneeling, and genuflecting before the electorate, seeking the sympathy of voters rather than demonstrating an understanding of the plight of those constituencies and how they will apprehend those challenges.

The Way Ahead!

Meaningful election reforms are challenging to spearhead because such legislative initiatives affect the current role of MPs. So they’re going to disregard them. Self-preservation is a human instinct for survival, and few will blame them for rejecting reforms which affect their livelihoods.

The Parliament has allocated powers to herself to raise wages and other perks. No wonder the tapering system of ensuring the wage difference between the highest-paid public servant and the least-paid public servant is minimal has been razed into a gutter. Tapering of wages, which became popular during Nyerere’s rosy years of equitable distribution of wealth or, as others later ridiculed, poverty maldistribution, took centre stage.

Today, the ratio of the minimum wage to the salary of an MP gross every month has hit an astronomical height of 106. To every Tanzanian shilling, the least paid Tanzanian who earns a paltry Tshs 150 000/= per month, an MP takes Tshs 106/=, meaning the MP makes 106 times compared to the least paid Tanzanian.

As the remuneration of MPs skyrockets, the carpetbagging reforms become an arduous task to institute because the stakes are very high. The winners and losers have too much to contemplate. As a result, such reforms are unthinkable yet urgently needed if we have to avert misplaced representation.

As the proportion of carpetbaggers grows in Parliament, the electorate’s problems become secondary and blurred as their representatives prioritize the issues they confront wherever they dwell.

In a more damning example, Dar-es-Salaam has the most significant number of carpetbaggers. No wonder the problems of Dar-es-Salaam are prioritized at the expense of others. This leads to regional unequal development and an exacerbation of socioeconomic tensions.

A genuine effort to attack this problem and consider constitutional provisions is recommended. We need articles of the Constitution to fix this bizarre problem of misrepresentation. We need residency requirements before one seeks public office. We suggest one has to be a permanent resident in that constituency for at least five years as a qualification to be a Councillor, an MP or a presidential candidate.

Paradoxically, the fears of our political class nurse of the threat posed by the diaspora to unseat them will be pleasantly resolved. Instead of crafting laws that dole out special citizenship status to the diaspora to deprive them of political rights, residency requirements will do a much cleaner job than diluting their constitutional citizenship rights.