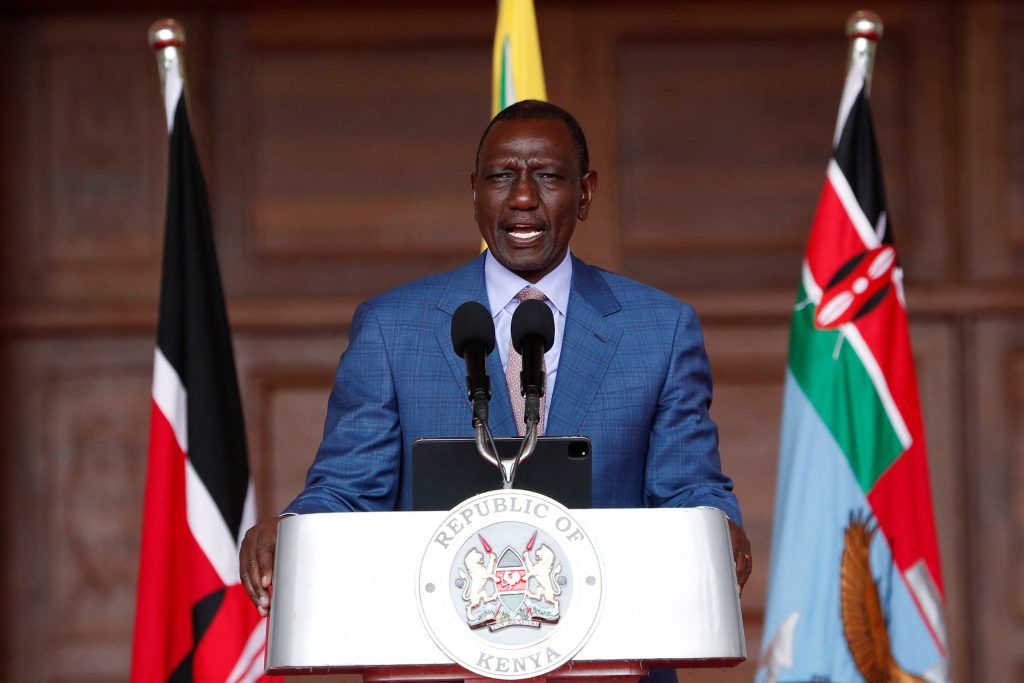

President William Samuoi Ruto of Kenya had toyed with the idea of forming a national unity government, breaking away from his campaign pledge that he would not entertain the opposition in his government. Now, at least four members of the main opposition party, the ODM, have joined his cabinet, holding key ministerial portfolios such as finance, minerals, and cooperatives.

Before becoming President of Kenya, Ruto endured a snub from his boss, Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, over what was known as a “handshake.” Uhuru Kenyatta is facing a bitter election dispute that was resolved by the Supreme Court of Kenya, which did not quell the dispute but took a frightful twist of “demos.”

Kenyatta later accused Ruto of standing in the way of lowering the political temperature between his political coalition and the ODM. Kenyatta did not incorporate ODM directly into his cabinet. Still, quietly, ODM had a say in the election commission and some powerful ministries as later Ruto and his allies named the ODM intruders “COVID-19 billionaires”. This discussion looks at the pros and cons of the government of national unity and assesses how the Kenyan Gen-Z have fared after this new development.

The Government of National Unity Betrays Multiparty Democracy

During the first term of the Mwai Kibaki presidency, President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni of Uganda remarked that Kenya was backtracking on multiparty democracy after Kibaki and Raila Odinga formed the first government of unity. Museveni noted: “…naona sasa mmmerudi kwenye mfumo wa chama kimoja….”

Multiparty democracy was considered to usher in a new era of competitive politics and accountability. During one-party rule in Kenya, political and human rights activists joined hands to campaign for multiparty democracy. Some lives were sacrificed in that fight, but President Daniel Arap Moi ultimately ceded ground, and constitutional reforms were carried out to open the door to political pluralism.

READ RELATED: Ruto’s Cabinet Choices Reflect Africa’s Wider Political Challenges

No sooner was multiparty democracy permitted a major political party called Forum for the Restoration of Democracy – Kenya (FORD-Kenya), which was considered to have a credible path to unseat Moi, was embroiled in tribal skirmishes between the Luo kingpin Oginga Odinga and the former finance minister Kenneth Matiba who was Gikuyu. Between them, each wanted to be the Presidential flag bearer of FORD-Kenya.

Once it became clear that neither had the full support of senior party members, Matiba left FORD-Kenya to form FORD-Asili, and Oginga moved to FORD-Kenya.

When the votes were counted in 1992, Moi triumphed, but the lesson was learned: the combined votes of the opposition exceeded the votes Moi garnered. Later, Kibaki, who trailed Moi, Ken Matiba, and Oginga Odinga through his political vehicle, the Democratic Party, reminded politicians in 1997 that Kenyans wanted them to unite and form a formidable opposition. Before that, Kenneth Matiba had thrown his voter registration, effectively losing the qualification to gun down the presidency.

In the 1992 election, Matiba believed he was rigged out and could have won if the election had been free, fair and credible. With the Kenyan Election Commision reforms a no go zone, Matiba did not want to offer credibility the elections of 1997, hence he opted out leaving Mwai Kibaki as the defacto leader of the Gikuyu.

I may add that Ken Matiba’s withdrawal from Kenyan elections unwittingly unified the Gikuyu vote under Mwai Kibaki, increasing his chances of winning future elections.

The 1997 elections left Kibaki second behind President Moi. Kibaki complained about a similar situation that had irked Matiba: The Kenyan Election Commission could not guarantee free, fair, and credible elections. Moi’s presidential two-term limits prevented him from running in 2002, paving the way for his successor, Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta.

Moi had invested heavily to ensure KANU won the 2002 elections by enticing Raila Amolo Odinga and all members of his Labour Party to join the Kenya African National Union (KANU). It was renamed to showboat a new era in Kenyan politics.

Paradoxically, President Moi tried to achieve what FORD-Kenya had failed to do a decade earlier: unite Kenyans under one umbrella and form a winning team. However, the party’s dilemma perturbed KANU too: who will be the KANU presidential flag bearer in 2002?

No sooner had Moi settled on Uhuru Kenyatta than KANU was in disarray, with Raila Odinga leading the stampede to join a new political party, National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), which another opposition luminary, Charity Ngilu, had formed.

While many reasons were shared about Uhuru Kenyatta’s unsuitability as president, the real reason was a protest against political dynasties taking over Kenyan political space. Uhuru Kenyatta was the son of the first president of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta. According to one Kenyan daily, it was said the Luo would not have allowed Raila.

Odinga to support another Kenyatta. So, the opposition was not tribal-related, as the KANU exodus benefited a Gikuyu Mwai Kibaki at the expense of another Gikuyu Uhuru Kenyatta, whose family had reigned over Kenya after independence. Others accused President Moi of plotting to keep the presidency rotating between his family and the Kenyatta one.

The election of 2002 left KANU presidential candidate Uhuru Kenyatta picking one vote to two votes Mwai Kibaki got. After coming to terms with his political gamble, President Moi had backfired. He ate a humble pie and instructed Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta to prepare a concession speech and read it before KBC TV.

NARC was ecstatic and marched to form a new government that was later embroiled in corruption charges all day in office. One British ambassador in Nairobi was so disgusted that he made a public statement about it, accusing the Mwai Kibaki government of eating public resources and spewing it in their feet.

It was a comment that many Kenyans took literally but did not understand its context. It was a figurative language aimed to drive a gist of the matter home. But it was not so, as Kenyan commentators took a swipe at the recolonization of Africa that was not the purpose at all.

In its first term, the Kibaki administration was consumed by infighting and official graft. Kibaki did not remove most ministers but kept shifting them to assuage public outcry. In the following election, Raila challenged Kibaki, whom he had endorsed in 2002.

Many international observers regarded the 2007 election as fraud, partly because Mwai Kibaki strongholds in Mount Kenya delayed bringing results until all constituencies had handed over theirs. At one point, the Kenyan election commission chairman threatened to announce the results he had if central Kenya did not hand him their results.

On the same night, the Election Commission Chairman announced Kibaki had won through KBC Television, sparking election violence that had led to the deaths of thousands of innocent lives. Later, a reporter queried the election chairman whether he knew with certainty Kibaki had won the election fair and square; he conceded there was no way he could have known.

On its own, that became a rallying point for Raila and his ODM troops to claim their victory was stolen from them. It was an election that many still suspect that Raila had probably won because of the Kalenjin people’s vote. William Ruto had helped to marshal their political party, ODM.

Even today, the composition of the Kenyan Election Commission remains unfinished as stakeholders fight to get their people inside it to influence the elections. Several reforms have been made, from clipping the president’s appointment powers and handing them to the parliament to crafting laws that will identify stakeholders who can elect their representatives there.

In all these cases, there was one drawback: what to do with multiparty democracy that allows the election victors to take the whole platter, leaving the losers in a sense of isolation and bitterness.

There are no straightforward answers because accountability is the chief loser if you bring election losers into the government. The opposition behaves as a party in power where abuse of power, theft and looting are defended lest parliamentarians burn their political careers. Efforts to have a prime minister from the opposition would attract its problems.

Stability may be the ultimate price to pay, as was seen during Mwai Kibaki’s second stint with Raila Odinga as his prime minister. As Raila had argued, the question of two principals brought a government to a standstill.

Every decision Raila made as Prime Minister wanted to be involved in, and when his views were rejected, he took the matter personally. He undermined the very government he was serving, creating fissures that were impossible to seal.

Uhuru Kenyatta’s ten-year reign avoided directly bringing the opposition to his government. However, in his second term, he unofficially permitted them to exercise power from outside, keeping them under a leash.

Kenyan politics has shown that loyalty must be bought, and nothing comes for free. A national government affords well-connected politicians a seat at the high table and a meal. It is not about combining similar policies or supporting causes closer to heart.

No sooner had President Ruto appointed ODM luminaries to key government jobs than Raila succeeded in wedging a crack in the President Ruto coalition. Those whom the government has sacked feel cheated and abandoned.

Their support was based on the understanding that they would be placed in positions where they could place their straws and enjoy the goodies. It looks like being in opposition has a better payoff than being in the ruling coalition.

The Gen-Z have few options now despite claiming they were tribal less. Now, their true colours will come to the fore. As Kalonzo Musyoka, a key figure in the opposition Azimio coalition, was addressing the press, citing his opposition to the “Nusu Mkate” deal, unruly youths, mostly belonging to Gen-Z, interrupted his press conference, breaking chairs and demanding he and his entourage to leave.

READ RELATED: Gen Z Leading Political Change in Kenya: What Does It Mean for African Politics?

Fearing for their lives, Kalonzo left with his fellows. Azimio is more damaged goods than Kenya Kwanza of President Ruto. The Gen-Z must return to the drawing board because everything they fought for is unstuck.

The new Finance Minister from the ODM before was appointed and urged higher taxes to fix the national debt. So, it is possible that the rejected Finance Bill 2024 could be restored with minor amendments like land and house taxes off the table.

It looks like President Ruto has found a formula to reinstate most of the Finance Bill 2024 by insulating himself behind Raila Odinga’s ODM, which has already declared is now supporting President Ruto’s government after his political allies will now be holding key ministries unthinkable a few weeks ago.

There is not even a single member of the Gen-Z fraternity among the four ministers Raila has appointed in the cabinet. Like most demonstrations to push for political changes, the youth bear the brunt while the elders watch them on living room TVs before enjoying the toil they never sweated for.

In most political drives for change, those who stay at home are more likely to benefit than those who risk their lives on the streets. President Ruto had promised Gen-Z to implement their suggestions, but they clearly see they have been taken for a ride.

Opposing the Ruto government going forward will divide Gen-Z into two factions, exposing the gap between aspirations and harsh realities.