As I previously wrote on my blog, electric vehicles (EVs) are rapidly proliferating across the world. However, the same cannot be said for some developing markets, including Sub-Saharan Africa. Essential infrastructure for EV success, such as reliable electric grids, EV service capacity, and charging stations, is still lacking in many parts of the region.

Focus on applications where you maximize the benefits while minimizing the problems

However, there are some very good applications for EVs right now that can play a role in bringing this new technology to the African market in a commercially viable way.

In this regard, I believe EV applications Africa should look to emulate are closer to what you may find in India around functional utility and cost savings than what you find in the US or Europe where they are more focused on luxury.

Why are EVs attractive as a transport solution? Benefits can include lower fuel and operating costs, limited maintenance and reduced carbon emissions depending on the source of electricity.

In other words, lower cost of transportation based on the application and the availability of electricity. Can these benefits be realized in African markets? It’s possible, but any effort to deploy EVs in Africa will require careful consideration given the inherent challenges.

First, consider some key characteristics of African markets that will limit EV adoption:

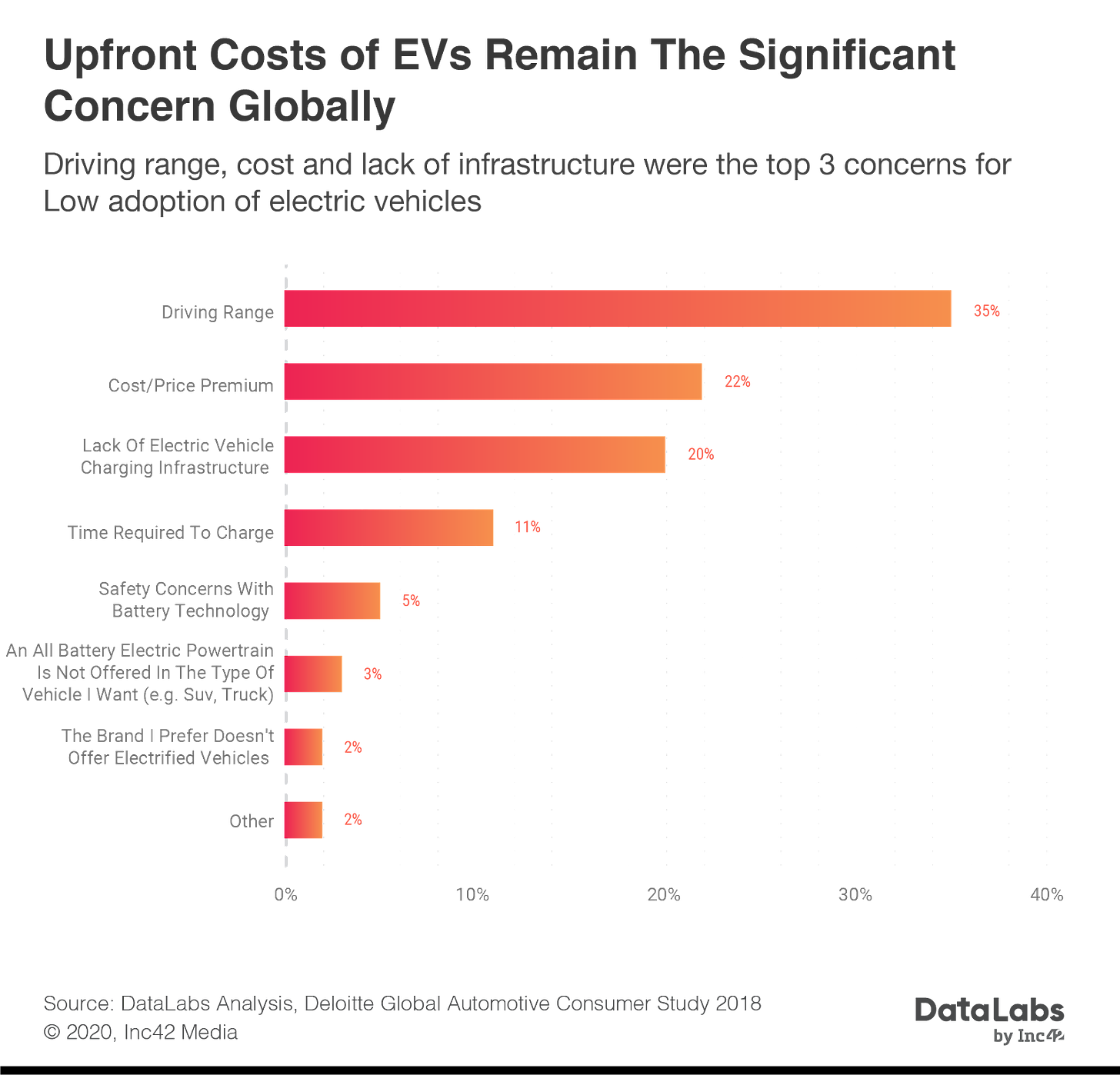

High Upfront Cost: EVs can initially be more expensive that comparable vehicles. Anywhere you see EV adoption at scale, you also find some sort of subsidy in place. You will not find mass adoption in Africa with out some kind of similar regulatory support.

Limited and unpredictable electric grids: EVs require immediately dispatchable power given their limitations on range. Intermittency of power supply can make EVs unreliable. Limited availability of the grid across the country means that there will be areas or regions where an EV will not be able to operate.

Limited Charging Infrastructure: If the grid is not available everywhere, especially in rural or peri-urban areas, it means charging terminals will not be available throughout the country.

As a result, EVs travelling longer distances (150 KM or more) from an urban centre will face challenges finding places to charge or will not be capable of making the trip. Charging infrastructure will also take time to build, so any early adopters will need to have their own charging solutions.

Lack of Service Capacity: While EVs operate with fewer moving parts and in general require less maintenance than regular internal combustion (IC) vehicles, basic service infrastructure is required. Lack of spare parts supply chains will mean early users will face challenges with extended repair times.

Given these constraints, I think mass-market consumer EVs in Africa as a commercially viable means of personal transport are still a ways off. Upfront costs are high.

Consumers accustomed to convenience will be regularly frustrated with their inability to use the vehicle when they want during a power outage or to travel extended distances. Supply chain problems will mean a major investment for a family (their vehicle) can be unusable for extended periods of time.

Assuming the constraints above, some EV applications can be effective in such an environment. In particular, fleet vehicles such as delivery trucks, buses, and other vehicles that operate defined urban routes and return to a centralized charging/parking location can take advantage of the benefits while avoiding problems associated with poor EV infrastructure.

With respect to benefits:

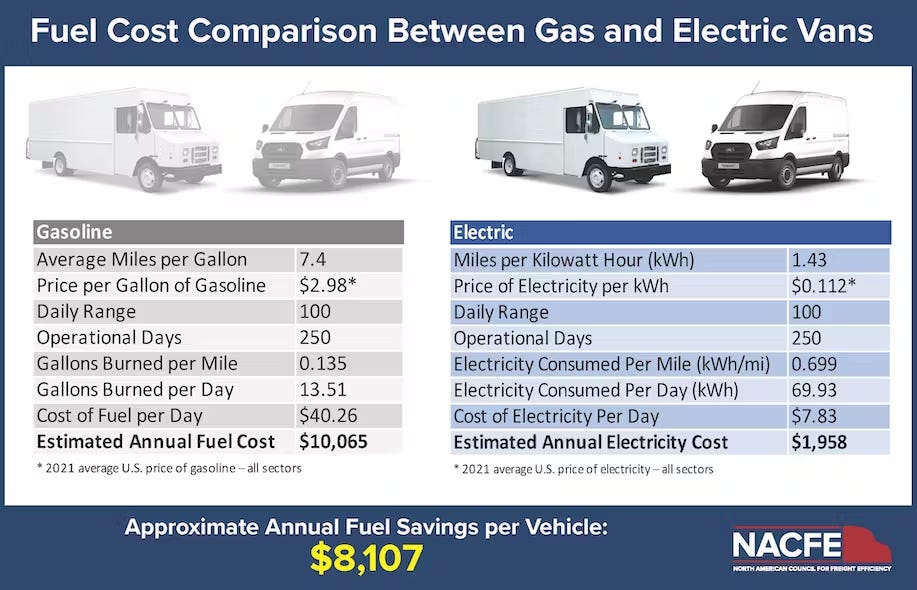

First, most fleet vehicles spend a lot of time in traffic. This means wasted fuel. EVs more efficient than IC vehicles because they only use power when needed. Idling in traffic dramatically reduces the fuel efficiency of IC vehicles while idling does not impact electric cars.

Furthermore, the nature of fleet vehicles is to operate every day for extended hours, under this usage profile EVs will maximize their operational savings. In other words, the more you drive an EV, the more you save vis a vis a comparable IC vehicle assuming lower maintenance costs.

Second, fleet vehicles necessarily return to the same depot location on a regular basis. Delivery trucks will return to a warehouse for picking up the next order. Buses will return to their parking yard at the end of the day.

This means charging infrastructure can be centralized in one location, eliminating the need for distributed charging points across the city or for a well developed charging infrastructure. These vehicles can also charge at night, avoiding intermittency issues associated with the electrical grid common during the day.

Third, in African markets not only is fuel relatively more expensive than in other parts of the world, it is also costly to manage. Fuel theft is an endemic problem associated with the transport sector. EVs would eliminate fuel theft and fuel handling costs, a major headache for transport operations.

Finally, vehicle fleets can justify the cost of internalizing maintenance infrastructure and keep spare parts in stock to ensure smooth vehicle operations. Unlike consumers who must rely on third party service providers, companies operating fleets can afford to self manage supply chains better.

In total, fleet vehicles avoid some infrastructure challenges facing EV vehicle adoption by centralizing operations and utilizing vehicles within defined routes within an urban area. Fleet vehicles can be an ideal entry point for EVs in Africa.

However, the potential success of EVs within fleet applications will depend on the overall cost. No amount of operational cost savings will be meaningful if the upfront capital cost is prohibitive. To address this concern, one thing African governments can do is relax import duties on EVs relative to the cost of importing IC vehicles.

The entire EV industry across many parts of the world was jump started by massive government subsidies and tax incentives. Tesla, more than a decade into operations, still benefits from a $7,500 Federal Tax Credit (this means it eliminates $7,500 of tax payments to the federal government for that consumer in that year) – in some cases almost 25% of the overall vehicle cost.

To expect EVs to flourish in African markets without some regulatory support is unrealistic. At the same time there are also benefits to EV adoption for regulators to consider, including reduced dependence on expensive imported fuels, reduction of urban pollution and sparking a transition to a vehicle technology ultimately well suited for African markets given traffic congestion and the problem of fuel theft.

African governments have pressing fiscal priorities. Subsidizing nationwide EV charging networks is probably not at the top of their list. But not being able to invest in EV infrastructure does not mean supporting EVs is not possible.

If EVs attract relatively less import taxes compared to their IC alternatives, reducing their overall capital costs and making them an attractive option for certain kinds of vehicle applications that can be financially sound investments without any further government support.

The introduction of EVs via fleet vehicle applications I believe can hold significant promise in jump starting the sector. In order for people to believe in the potential of EVs they need to see them operating on the ground effectively and at a price point that makes economic sense for adoption. Only then will we see uptake.

There are real, legitimate potentially viable applications for EV adoption in Africa right now. At Sarafu, a B2B ecommerce company delivering to the last mile, we are actively exploring option.

Taking a wholistic, realistic view with targetted regulatory interventions can align business and economic interests in a way that can bring new technologies to Africa for the benefit of consumers, businesses and governments alike.

Read more article from Firas Ahmad here.