The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is often presented as a core indicator of economic prosperity. This metric, calculated by dividing the GDP of a nation by its population, provides a per-person average that implies the country’s economic standing on a global scale.

However, GDP per capita paints a broad and sometimes misleading picture of actual economic realities, especially in countries with significant income inequality and diverse demographic profiles. When examining African nations—where income disparities and poverty levels are acute—the weaknesses of GDP per capita as a sole metric of growth become glaringly apparent.

Tanzania, with an economy growing at an average rate of around 5%, exemplifies the complexities behind GDP per capita, revealing the struggles that citizens face amid rising inflation and a high cost of living.

The Superficial Wealth of GDP per Capita: Masking Income Disparities

GDP per capita has an inherent flaw: it presumes an even distribution of wealth across a nation’s population. Yet, in most African nations, economic growth is disproportionately shared, with wealth concentrated in the hands of a small elite while the majority remain impoverished.

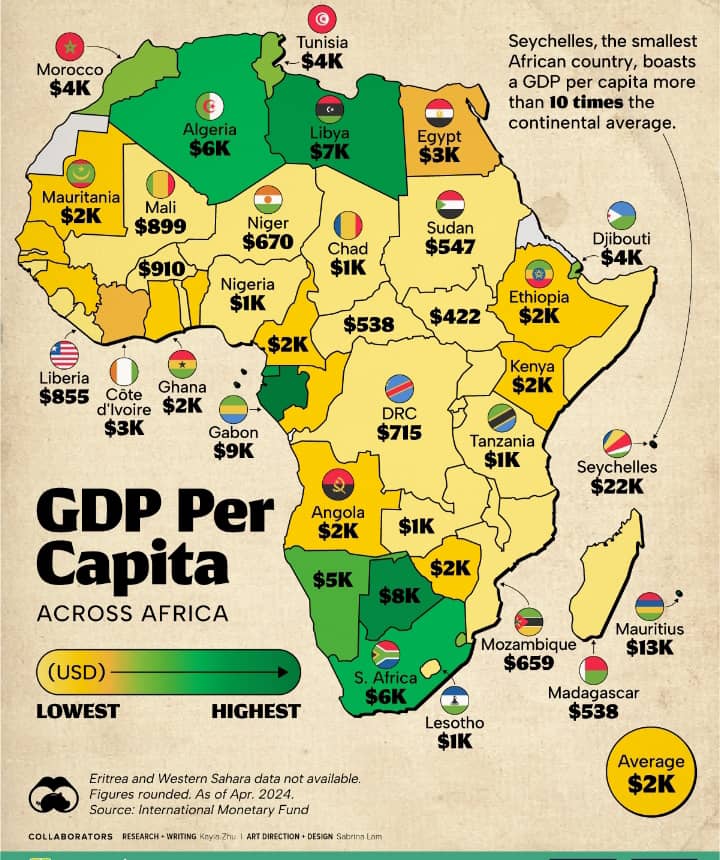

For instance, Seychelles and Mauritius, with GDP per capita figures of $21,875 and $12,973, respectively, appear wealthy by African standards.

These nations benefit from thriving tourism sectors and offshore finance industries, boosting their economic standing. However, these figures obscure the challenges lower-income segments face in these societies, including limited access to affordable housing and healthcare.

In countries like Tanzania, where GDP per capita stands at a modest $1,220, the metric does not reveal the significant portion of the population living below the poverty line. While the economy is growing, this growth does not translate into meaningful improvements in the lives of many citizens.

Income inequality in Tanzania and across many African nations results in a skewed GDP per capita that exaggerates the average citizen’s actual prosperity. This gap between reported economic growth and on-the-ground poverty levels highlights the limitations of GDP per capita as an indicator of well-being.

Economic Diversity and Population Dynamics: The Case of Africa

Africa’s population dynamics add further complexity to the GDP per capita metric. With populations growing rapidly, many countries face the challenge of spreading economic gains across a larger populace.

Countries like Nigeria and Ethiopia, for example, boast large economies with relatively low GDP per capita figures ($1,109 and $1,909, respectively) due in part to their large populations. High population growth often outpaces economic expansion, diluting per capita gains and intensifying poverty among the most vulnerable groups.

In Tanzania, the GDP growth rate of around 5% fails to keep up with the demands of a young and expanding population. High population growth, coupled with significant rural-urban migration, strains infrastructure and services, limiting the reach of economic development to urban centers and leaving rural areas marginalized.

Consequently, the benefits of economic growth are concentrated in urban hubs, while rural residents remain excluded from progress, perpetuating the cycle of poverty.

Inflation and the Cost of Living: A Growing Pain for Tanzanians

Tanzania’s experience with inflation further highlights the inadequacies of GDP per capita as an indicator of economic well-being. Recent inflation in essential goods, such as food and fuel, has directly impacted citizens’ purchasing power, aggravating the cost of living.

As a result, Tanzanians struggle to afford basic necessities despite the country’s positive economic growth metrics. This disconnect between GDP per capita and the lived experience of Tanzanian citizens illustrates how the metric fails to account for inflation’s erosive effects on real income.

High inflation rates in essential goods exacerbate income poverty as wages stagnate and real purchasing power declines. Even in a growing economy, citizens find it increasingly difficult to meet basic needs, underscoring the limitations of GDP per capita as a measure of actual economic health.

In this context, GDP per capita appears as a distorted indicator, obscuring the economic struggles of ordinary citizens who bear the brunt of inflation and rising living costs.

The GDP per Capita Dilemma: A Call for Comprehensive Metrics

The GDP per capita metric’s inherent limitations raise important questions about accurately gauging a country’s economic health and prosperity.

In Tanzania, as in many African nations, GDP per capita alone does not account for disparities in income distribution, population pressures, and the escalating cost of living.

While GDP growth may reflect increased national production, it often fails to capture the quality of life experienced by the population. For this reason, there is a growing need for alternative metrics that more accurately reflect economic well-being and inclusivity.

One alternative is the Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality within a nation. Countries with high GDP per capita and high Gini coefficients, such as South Africa, highlight the paradox of wealth alongside significant inequality.

Other metrics, such as the Human Development Index (HDI) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), provide a broader view of economic prosperity by incorporating health, education, and living standards.

These indicators offer a more comprehensive assessment of economic progress and better reflect the realities citizens face.

Conclusion: Rethinking Economic Success Beyond GDP per Capita

While widely used, the GDP per capita metric is an imperfect measure of economic growth and individual well-being. In African nations, where income inequality, population diversity, and inflation are prevalent, the limitations of GDP per capita become especially stark.

Tanzania’s experience illustrates how a country can exhibit economic growth yet fail to translate this growth into improved living conditions for the majority of its population.

For policymakers and economists, the challenge is to move beyond GDP per capita and adopt metrics that more accurately reflect the distributional and qualitative aspects of economic growth.

By considering alternative indicators that account for inequality, inflation, and the cost of living, African nations can better evaluate their progress and ensure that economic gains reach all citizens rather than remaining confined to a privileged few.

Only by addressing the dark side of GDP per capita can African countries truly achieve sustainable and inclusive growth that benefits their entire populations.

Read more articles from Steven Mmbogo here.