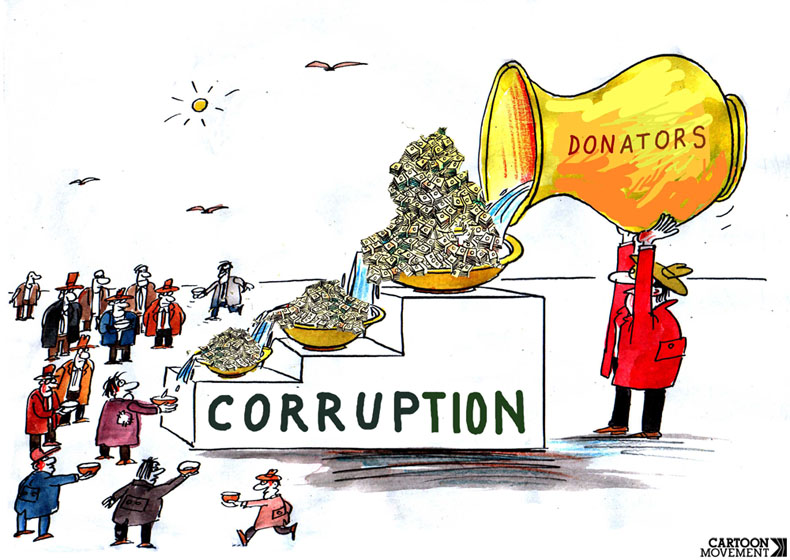

East Africa faces various challenges, including dictatorships in Rwanda and Uganda, tyranny in Tanzania, tribalism in Kenya, and civil war in Sudan and DR Congo. Corruption, a regional issue, remains ‘one of the major obstacles undermining both short- and long-term development’ (IG, 2021).

Every government in East Africa suffers and grieves the symptoms in every sphere; private sector corruption is irregulated, and government agencies have failed to devise reasonable strategies to counter it.

Since some cases of corruption and its cost “are harder to express in exact monetary terms” (IG, 2021), people and authorities tend to ignore them.

On the other hand, corruption in the public sector is controllable and regulated but depends on the commitment of the executive organ. “The actor bearing the cost is the society at large or the government” (IG, 2021).

As long as citizens continue to pay taxes to fund projects that will never be completed or pay foreign debt, the money will end up in the hands of few.

This article intended to explore the weaknesses of the legal and institutional framework on corruption in Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda, which resulted in “Reducing citizen’s trust in public institutions,” “poor infrastructure, delays in project implementation, and low investment,” as asserted in the fourth National integrity survey report in Uganda.

RWANDA

The Republic of Rwanda is one of the cleanest countries in Africa and the world; it is popular due to factors like its democratic practices under military governance, involvement in engineering civil wars in DRC and the 1994 Genocide.

“Research has shown that accountability, transparency and citizen participation are key elements to sustain the control of corruption… Rwanda tends to perform significantly worse than it does in the fight against corruption” (Bozzin, 2013).

My problem is, “International experience shows that corruption can not be combated as an isolated phenomenon” (Commission of Inquiry Burundi, 2021); how did Rwanda handle corruption single-handedly?

READ RELATED: Can the Judiciary Truly Be Independent When Politicians Pick the Judges?

Without hesitation and with strong evidence from consolidated democracies worldwide, Alessandro Bozzini (2013) finds a “strong correlation between democracy and corruption.”

It is believed that “political democratisation is associated with a lower level of corruption”.

Through Rwanda, democracy has been challenged not to be the only solution to corruption since corruption is “almost non-existent in Rwanda” (Transparency Rwanda, 2009), and Singapore is a counter democracy of the world, “Rwanda authorities often quote as their model”.

The Constitution of Rwanda, as amended in 2003 and recently amended in 2023, is the cornerstone of justice, accountability, and ethics for public servants; however, it does not have specific provisions to entrench anti-corruption strategies and initiatives.

Articles 29 and 64 of the Rwandan constitution directly entrenched democratic principles, indirectly denouncing corruption in public service. Integrity, public interest, accountability, transparency, and good governance are the features that public officials must comply with.

However, it is “impossible for citizens to hold the government accountable for its management of the public’s money… citizens participation” is often directed and controlled by the authority” (Bozzini, 2013).

Due to the specificity of these two articles, private sectors in Rwanda stay in a safe zone. Integrity and public interest might not be necessary, transparency is optional, and accountability is unquestionable.

“Launched sensitization campaigns to raise the population awareness on the negative consequences” (Bizzini, 2013) of corruption serve an important function to ensure the common good.

Articles 70 and 168 focus on empowering independent institutions and establishing the Supreme Court with jurisdiction over corruption, respectively.

Empowering anti-corruption institutions replaces the fight against corruption with one man’s ambition, a commitment of executive organs, or political will to competent and impartial agencies, even though political will is a potential factor in Africa.

These articles aim to empower institutions to investigate and adjudicate corruption and maladministration. Barely depending on intimidation strategies to combat corruption through fear, “petty corruption is far from eradicated and studied. The police and local authorities tend to be the institutions most exposed. Forms of non-monetary corruption are not unknown either” (Bozzini, 2013).

Fear is not a reliable measure for long-term use, especially when the most feared man in the country is no longer there, just like how Magufuli’s anti-corruption strategies stumbled after his death, resulting in the rebirth of corruption and innovative ways to steal public property.

“You also bring money from Tanzania by road, then come and start constructing buildings around here. That is what people do,” asserted J Mbadi, a National treasury cabinet Secretary at the 52nd EARACG hosted by KRA 2024.

Kagame’s zero-tolerance policy might be effective. “A note of caution is needed here, as many indicators are based on surveys carried out in the country. It must be noted that some analysts are sceptical of the reliability of the findings” since very few victims of corruption report the occurrence to relevant institutions”.

However, “Gender-based corruption in the workplace” (2011) showed that 5% of Rwandans have experienced gender-based corruption, while almost 20% know someone who has been a victim. Bribery is still present, non-monetary forms of corruption seem to be well established, and reporting is very low.

The long-term strategy depends not on one man’s willingness but on institutions and procedures that change, not personal desire. Rwanda may have much to learn from the late President John Magufuli and his leadership behaviour.

The Supreme Court and the Office of the Ombudsman may have an effective role in the private sector, but again, the detection and prevention of corruption is technically impossible if they solely depend on intimidation strategies.

Who cares what laws say if the president constantly amends them to fit his greed for power?

Corruption law no. 54/2018 of August 2018 on the fight against corruption came to bridge the Rwandan constitutional deficiency of articles 70 and 168 by acting as the primary law against corruption.

The most significant role that this law plays is not penalties and fines but defining corruption and preventive measures that give real power to institutions.

Its comprehensive nature allows the public and private sectors to be checked through parameters that Foster citizenry interest. “Some analysts believe that such cases might also serve the purpose of removing personnel who are out of line politically” (Bertelsmann, 2012).

BURUNDI

The Republic of Burundi is one of the smallest and unpopular countries in Africa, the due factors are; it is landlocked country, unpopular democratic practices, scarce resources only fit to sustain Burundian and its 165/180 corruption rank in 2020 by transparency international’s corruption perception index.

According to Salvatore Schiovo (2006), in a research paper titled “Fight Corruption and Restoring Accountability in Burundi; produced by Nathan Associate Inc., corruption in Burundi has been exposed, and the system has been challenged to ensure practical solutions are embraced as follows;

“Corruption is reportedly everywhere, making it very rare for citizens to obtain government services to which they are entitled, or licenses and permits, without paying bribes” from public to private institutions. It has become the fashion people embrace to get the service they deserve.

“External aid has often provided openings for corruption” in Burundi and countries like Kenya, Tanzania and Cong DR.

“The most extreme case is the disappearance of large sums from the state treasury on the occasion of the transition from the interim government to the newly elected government of President Nkurunziza in August 2005” also happened in Tanzania in 2021 after the death of the late president John Magufuli and the occasion of transitioning power to his vice president.

The Burundian constitution of 2018, which replaced the 2005 constitution, does not contain sections or chapters that directly denounce corruption in public.

However, article 146 demands the declaration of assets when assuming or leaving office. The president’s ambiguous position on corruption resulted in “inconsistencies and reversals about the implementation of the state officials’ constitutional obligations to declare their asset” ( commission of Inquiry Burundi, 2021)

article 151and establishment of independence institutions such as the Special Brigade Anti-corruption Commission of Burundi, the Court of Auditors and the Anti-corruption Court, among many others, encroachment or overlapping of functions is very common among anti-corruption agencies in Burundi to the extent that corruption detection, prevention and combative strategies provide ineffective and weak implementation since some agencies received limited resources or opt not to engage fully in the fight, for example, the National Public Procurement Control Directorate and the Public Procurement Regulatory Agency operating under Public Procurement law solely focuses on minimise corruption not combating. However, the extent of minimising is numerically debatable.

Constitutional provisions that set ethical standards for civil servants and provide guidelines for their conduct on the one hand and anti-corruption law on the hand believed in providing relief on the corruption situation of the country, proving inefficiency due to the presidential “declaration that he accepts officials taking bribes to contribute to the development of the country” (commission of inquiry Burundi, 2021), lack of transparency, political interference and limited resources.

The primary legislation in Burundi, law no. 1/12 on preventing and punishing corruption and related offences is unique in the fight against corruption. It defines forms of bribery and prescribes penalties.

The unique part is its detective measures, which constitutional provisions on anti-corruption articles have not. However, the effectiveness of detection measures is questionable.

Law no. 23/2003 related to the punishment of corruption and exclusively criminalise corruption for public and private servants.

UGANDA

One of the biggest countries in East Africa, its president is dying to be the first president of the East African Federation.

Uganda is famous for its Charismatic Idd Amin Dada, the long-lasting President Museveni, civil wars in the northern part, and its dedication to uniting East Africa.

“Uganda has been a signatory of the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) as well as of the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption since 2004″ (Maira, 2013).

The Ugandan Constitution is similar to that of Rwanda and Burundi. It does not have a specific section or chapter dedicated to ending corruption; however, it has provisions that directly rebuke corruption.

Article 38 of the Ugandan constitution, adopted in 1995, is similar to Article 29 of the Rwandan constitution; good governance, transparency, and accountability principles are believed to allow no gap for corruption to occur solely in public sectors.

Private hospitals, schools and industries enjoy the freedom that this article ignores.

Articles 115 and 120 of Uganda entrenched the significant independent institutions and offices that empower to ensure justice and fairness for the common good, for example, the Inspectorate of Government (IG), strengthened to investigate and prevent corruption only in the public sector, and the Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and anti-corruption court bridge the weakness of (IG) to include private sectors in detection, prevention and combating corruption.

However, Uganda’s primary legislation countering corruption is the Anti-Corruption Act of 2009, which defines corruption, prescribes penalties and outlines detection and prevention measures.

The Act also supports public procurement and disposes of public assets. Under this Act, public procurement is regulated and managed to minimise the possibilities of corruption channels.

Overall enforcement in the fight against corruption in Uganda is ineffective; Transparency International Uganda: The global coalition against corruption provided that, “According to Freedom House, the government’s reliance on corruption to fund its expanding patronage network makes it difficult for it to punish members of the president’s inner circle” (Maira, 2013 (Freedom House, 2012b:14)).

Who cares what the law says if the president constantly replaces constitutional provisions to stay in office?

Anti-corruption agencies are suffocating due to the shortage of resources, “Other studies highlighted the alleged government effort to pass a supplementary budget to meet campaign needs” (Maira, 2013 (Barkan, 2011)) and difficult to access potential information to investigate since transparency is only paperwork and has no room in sit-tight syndrome systems like Uganda or Rwanda, political interference is empowerment by the myth that executive organ is a more entrenched pillar of the government.