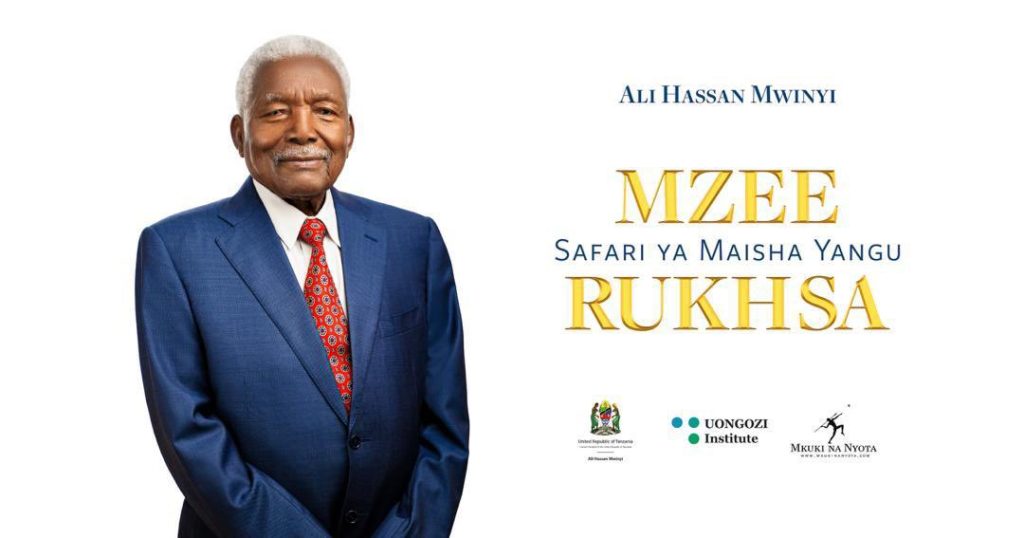

The passing of Former President Ali Hassan Mwinyi on 29th February 2024 was greeted with a mixture of sadness, aloofness and nostalgia. Sadness because we abhor death, no matter what it entails in the afterlife and the promise of reincarnation. Aloofness because he kept himself afar from the levers of power after retirement. So, few of us know anything worthwhile concerning him to recollect and parse through. And nostalgia because he left an indelibly mark in our public life. This article traces his life, challenges, successes, and, where possible, his low moments.

Mwinyi was born on 8 May 1925 in the village of Kivure, Pwani Region, where he was raised. He then moved to Zanzibar and got his primary education at Mangapwani Primary School in Mangapwani, Zanzibar West Region. Mwinyi then attended Mikindani Dole Secondary School in Dole, Zanzibar West Region. From 1945 to 1964, he worked successively as a tutor, teacher, and head teacher at various schools before deciding to enter national politics.

Concurrently, Mwinyi earned his General Certificate of Education through correspondence (1950–1954) and then studied for a teaching diploma at the Institute of Education at Durham University in the United Kingdom. Upon his return, he did not leave England until 1962, being appointed principal of Zanzibar Teaching Training College in Zanzibar West Region.

Ali Hassan Mwinyi married Siti Mwinyi in 1960, and they had six sons and six daughters. In retirement, Ali Hassan Mwinyi stayed out of the limelight and continued to live in Dar es Salaam.

Mwinyi died of lung cancer at the prime age of 98, and few can even contemplate. President Julius Nyerere retired in October 1985 and appointed Ali Hassan Mwinyi as his successor. Nyerere remained chairman of the ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) until 1990, which would later cause tensions between the government and the party regarding economic reform ideology. When the transition of power took place, Tanzania’s economy was in the midst of a slump.

From 1974 to 1984, the GDP grew at an average of 2.6% yearly while the population increased faster than 3.4% yearly. Despite Tanzania’s minimum wage laws, rural incomes and urban wages had fallen by the early 1980s. Furthermore, the currency was overpriced, basic goods were scarce, and the country had over three billion dollars of foreign debt. Agricultural production was low, and the general opinion was that Nyerere’s Ujamaa socialist policies had failed economically.

Mwinyi rose to power by accident because he was not in the succession line. The turmoil generated by the Zanzibar government’s joining the controversial Islamic Organization Council led to the forced resignation of the then president Aboud Jumbe, who paved the way for his coronation as the president of Zanzibar. Had there been no IOC turbulence, there was no credible route for Mwinyi to become the president of Zanzibar and, by induction, the president of Tanzania. It was all a matter of fate: being the right person at the right moment in our history of public service.

Prior to that, Mwinyi was applauded for resigning as the Minister of Interior following the deaths of remandees due to poor ventilation somewhere in Shinyanga. He was considered a leader who led by example, taking responsibility in a political culture where leaders rarely account for their failures or the shortcomings of their subordinates.

Mwinyi’s presidency in Zanzibar was short-lived, as Nyerere had decided to retire in 1985. In fact, according to Nyerere, he had wanted to retire in 1980. However, he was pressured to continue because the country was still recuperating from the aftermath of the war with Uganda. He quipped in 1980: how could I leave the nation in such a mess?

Read related: Lowassa’s Comebacks Were Derailed, But At Least Jakaya Kikwete Kept His Promise.

The choice of Mwinyi to become Nyerere’s successor in 1985 was not without hiccups. Some say Nyerere’s preferred successor was either Rashid Mfaume Kawawa, and others hinted it was the diplomatic Salim Ahmed Salim. Kawawa was quickly taken out of the matrix of succession politics because he was unpopular as a consequence of closing private shops to protect ujamaa shops that were underperforming. Some went as far as whispering that Kawawa was not presidential material and devoid of a pleasing personality!

Dr Salim was on the run, but Mwinyi got more votes than him in the CCM central committee. One of the members of the CCM central committee, Patrick Qorro, once confessed before the election of Nyerere’s successor, Mwinyi had asked him whom he thought would bag the presidency between Dr. Salim and himself, Qorro intimated to him that Dr. Salim would take the prize home. Dr Salim did not, and Mr Qorro had always regretted being too open with his views.

No sooner than Mwinyi was sworn in, it took him four years to dismantle the central committee or about two years after Nyerere handed him the CCM chairmanship. Qorro and the likes of Hassan Mwakawago saw their political fortunes dwindling before their own eyes. Mwinyi defended his stance by claiming members of the central committee were also doubling as ministers and deputy ministers, eroding accountability.

Qorro felt Mwinyi was punishing him and others for his lack of loyalty towards him. In fact, new Ministers such as Kighoma Malima doubled as ministers and members of the CCM central committee, defeating the whole notion of separation of party leadership positions from the government ones.

Where others were afforded a soft landing like being appointed as ambassadors, instancing Mwakawago was shipped to the US, Patrick Qorro was snubbed during the ten years of Mwinyi administration only for his buddy Benjamin Mkapa to revive his lacklustre political career in 1995.

In 1987, Mwinyi fired seven ministers for graft-related allegations. I remember vividly one minister who was being driven in a chauffeured Mercedes Benz saloon being booed by the onlookers in Dar-es-Salaam after getting the sack. That was no other but the then minister for natural resources and tourism. During that time, the tempo to rout out official corruption grew in leaps and bounds and Mwinyi was given an iron broom to clean up the mess in public service.

We all know now too well that Mwinyi left public service more corrupt than the one he had inherited from the founding father of Tanzania, Mwalimu Julius Kamabarage Nyerere. I may humbly add that the corruption war under the Mwinyi regime, just like after all of his successors, embellished style and spectacle more than substance.

Notably, Mwinyi would be most remembered for undoing Nyerere’s 24 years and eight months of centralized planning that led to major means of economy to be in the hands of the government. During Nyerere’s rule economic freedom was curtailed by the then famous Azimio declaration (Azimio la Arusha) that constrained public figures from owning rented houses or being directors in private companies, among others.

Mwinyi, in 1992, went to Zanzibar and revoked the Azimio la Arusha declaration with the Zanzibar declaration that effectively opened the door for public servants to own property and engage in private business simultaneously. While permitting public servants to own private property was more popular than today, that loophole has opened a door for power abuse and looting of public coffers. There is an inherent conflict of interest for public officers playing double roles as public servants and business people who may be competing with their employer, the government.

Through his economic relaxation motto, he became popular. Still, it was how he picked presidential appointees that drew the criticism of those who felt he was discriminating against Christians in favour of his own religion, Islam. This criticism is not new. Every president has been accused of favouring his own religion. Still, Mwinyi, since he was the first Zanzibari and Muslim to become president, endured harsher assessment on the matter than all combined.

His choice of the finance Minister, Professor Kighoma Malima, drew most of the venom because of the way Malima conducted himself. Malima was pompous, extravagant and an academic braggart. Mwinyi would also be remembered for handing the Loliondo Game Reserve to the Dubai military general. The polarizing issue of Loliondo is still raising acrimony and bitterness among the citizens and beyond, with one side agitating for the continuation of the lease while others clamour for it to end. The real benefits of the Loliondo lease remain unaccounted for to justify preserving the status quo.

Apart from superficial reforms, Mwinyi did not address core areas in our constitution recommended for reforms. Neither did he do away with the most repressive laws the Nyalali report had recommended.

How Will Tanzanians and The World Remember Him?

He will be remembered with nostalgia as a man who was at the helm during global rejection and soul searching of the central planning system and one-party rule. He was an enthusiastic reformer who carefully guided the transition from one political party to a multiparty democracy. He did not finish the job since time was not on his side to complete what he had started. He would also be fondly remembered for his respect for human rights and the rule of law.

For example, when in 1986, the University of Dar-es-Salaam students struck in protest of poor living conditions. He took time to invite their elected leaders for a cup of coffee at the state House and later, in public, conceded the issues the students had raised were vital to ensure they received the best education. It was such a demeanour of humility and sensitivity to the plight of the weak members of the society that his legacy has now been engraved in stone.

It was all a matter of fate: being the right person at the right moment in our history of public service🙌